The snow person produced by the little children, then, bears the scars and blemishes of its journey. As it melts, it sags and droops and shrinks until finally nothing is left but a puddle filled with pebbles, chunks of dirt, twigs, and perhaps even the droppings of a neighborhood dog. Such is the fate of this snow person made by the hands of little children. He or she, unlike a living human being, has no control over her inner life—in fact, she has no inner life to control. The upside to being a snow person, of course, is that snow people feel no psychic pain.

The downside to being a human is that, unlike the snow person, we do feel psychic pain. All the nasty little bits of emotional garbage we collect and internalize as we roll over our life’s path do their damage. What are these nasty little bits of garbage? They are all the toxic, devastating bits of emotional fallout from abuse and neglect. They are the hurts inflicted on us by adults when we are children, the hurts inflicted by our peers, and the hurts we inflict on ourselves. All these hurts do their damage, some damaging us more than others. Recently, I have stumbled across one of these bits of toxic fallout that has affected my own life more than most others. So what is this toxin called? It is called shame.

For decades I had read about the damage that shame does, how shame can affect self-esteem and cause a human being to feel worthless. However, no article I had read had given me much information that I could actually use to help myself. The articles told of the devastating effects of shame on a human being’s psyche, but they did not discuss possible origins of shame, the dynamics of shame, or give any clues as to how one manages to shed the toxic effects of shame. Furthermore, I did not identify shame as being one of the specific factors that had eroded my self esteem from the time I was a child.

Also, because I remembered being told by my mother innumerable times that I should be ashamed of myself for having done this or that, I reached adulthood believing that shame was tied only to certain acts that I had committed in childhood and later in adulthood and was not one of the more generalized but deeply-rooted poisons that interacted with other psychic poisons to produce my low level of self esteem, the belief that I was utterly worthless and completely unworthy of being in the company of other humans. Thus, until last week, I rolled over the path of my life largely ignorant of the role shame has played in perpetuating my C-PTSD.

If I ever had doubts about the value of therapy, my doubts evaporated last week! Why? Last week I met Shame head on and decapitated it, rendered it powerless! How, suddenly, did I do this?

First, a conversation between me and my therapist caused me to connect to some of my earliest childhood memories. I remembered when I was about three asking my mother at various times if I could sit in her lap, and I remembered that she always said “no” and always had a reason for her “no.” Sometimes she said no because I was “too big for that”; sometimes I was “too heavy”; sometimes she was too busy or too tired, and sometimes she wanted to smoke a cigarette and I would be in the way. Each time she turned me away, I felt sad. When I was an older child and clearly too physically large to sit on her lap, she complained about having to touch me or touch my hair when she got me ready for school. I remember her cracking me on the head with the hairbrush one morning when I squirmed, and I remember hearing her say, “I hate touching your hair.”

By then I must have achieved the “age of reason” because I remember thinking to myself, “Then why won’t you let me get my hair cut?” She hated touching my hair, yet she wouldn’t grant me my request to have short hair that I could brush without her help. I was smart enough to keep my question to myself; if I had asked her the question, she undoubtedly would have cracked me on the head with the hairbrush. Why did she dislike touching me, and why didn’t she seem happy to be with me?

As my childhood turned to pre-teenage years, my sadness grew, and accompanying the sadness came a new element, a feeling of not being good enough and a feeling of being ashamed because I wasn’t good enough. I felt angry at myself for being such a failure as a human being. If I had been good enough, I reasoned, my mother would have wanted to touch me and to let me sit on her lap. Mothers of my friends liked touching their little girls, letting them sit on their laps, and holding them close. And if I had been good enough, my mother wouldn’t have cracked me over the head with the hairbrush or frowned at me all the time she was getting me ready for school in the morning and at other times. She was never happy when I was with her, or so it seemed to me, because I was not the little girl she wanted. I was a chipped Spode teacup she had bought on sale and could not return: she was stuck with me, and she was not happy about that!

When I was a child, I was never able to come up with a specific answer to “What’s wrong with me?” If I had been able to answer the question, I might have tried to change whatever it was about me that my mother didn’t like. But I didn’t know what was wrong; therefore, I didn’t know what to change. By the time I was a young teen, I had given up on my mother, our relationship, and on myself. I had concluded that I had come into the world “wrong,” and there was nothing I could do about that. My shame was so overpowering that I often couldn’t look people in the eye when I spoke to them or when they spoke to me. When somebody hurt me, I didn’t fight back or complain because I felt I deserved being hurt. When my husband abused me, I felt I deserved his abuse and did nothing to stop his behavior. For the past thirty years, I’ve been on my own, not living with anyone who has been abusive, yet I have continued to feel unworthy, ashamed, unable often to look at people when they have spoken to me or when I have spoken to them.

All this has changed, however, in the past week. Suddenly I realize that there is nothing inherently wrong with me, and my sense of being undeserving and unworthy is simply gone. I don’t know where it went, but it’s gone. Just like that! Gone!

What brought about this change? A sensitive interaction between my therapist and me, for one thing. Also, shortly after this important therapy session last week, I typed something like “origins of shame” into Google and found an absolutely amazing article by Richard G. Erskine titled “A Gestalt Therapy Approach to Shame and Self-Righteousness: Theory and Methods.” (See link at the end of this essay.) And there it was—a description of how shame originates in a child, starting with a feeling of sadness that, like a snowball, develops into a sense of being inadequate and worthless as the child rolls along her life’s path. Not only does Richard G. Erskine describe the development of shame in a child, but he also describes the process by which shame lowers a person’s self esteem:

“Shame also involves a transposition of the affects of sadness and fear: the sadness at not being accepted as one is, with one's own urges, desires, needs, feelings, and behaviours, and the fear of abandonment in the relationship because of whom one is. The fear and a loss of an aspect of self (disavowal and retroflection of anger) fuel the pull to compliance - a lowering of one's self esteem to establish compliance with the criticism and/or humiliation.” Erskine [Italics and underlining are mine.]

All I could say to myself when I finished reading the article was, “Wow! He sure hit the nail on the head! Thank you, Richard G. Erskine!” For in that article, I recognized the process that had taken place within me, the process that began when I was very little and was told by my mother, “No, I want to smoke a cigarette” when I asked to sit on her lap and continued on when I as a wife allowed my husband to belittle and abuse me because I felt I deserved the treatment.

A dear friend of mine has told me repeatedly, “With awareness comes change.” How right she is! And now that I am fully aware of shame and its toxic effect on my psyche and my life, I feel change taking place. For one thing, during a family gathering on Christmas Day, I let a person in attendance know how I felt about her childish, rude, disrespectful behavior. Others had felt as I had, but I spoke out. I don’t know whether I made a difference by speaking out, but I know I felt better because I called the situation as it was and didn’t consider myself unworthy of speaking out. That was a first! The New Year, 2012, is almost upon us, and I’m wondering what the “second” will be—and the “third,” “fourth,” . . .

I feel that as a result of my newly-found awareness of shame and its effects on my life, I have leaped over a gigantic hurdle on my way to healing. I’m getting there! And so will you! If you are in therapy, take it seriously and work hard. If you are not in therapy, find a competent and compatible therapist who is skilled in treating clients with C-PTSD and PTSD. You are a human being, a person, and unlike snow people, you are capable of change and healing. See how many hurdles you can jump and how far down the road to healing you can travel in 2012!

Blessings and everything good to you in the New Year.

Jean

(URL for Richard G. Erskine's article: http://www.integrativetherapy.com/en/articles.php?id=30)

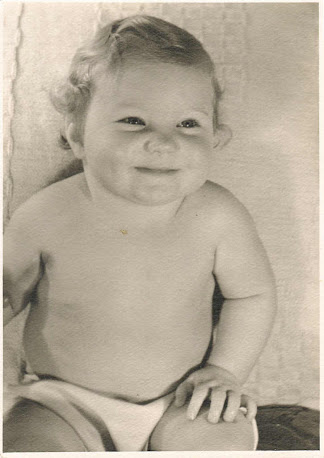

Before Shame