In my last post (Developmental Gap?? What’s That??) I discussed developmental gaps and attempted to define the term as I know it and as it appears to apply to me. The gap I identified in the previous post is the gap I call “lack of connection.”

My parents took good care of me, as the owner of a Porsche takes good care of his or her vehicle. When I was an infant, they fed me, changed me, and, just as the book recommended, they left me in my crib for four hours between feedings and changing. When I was a toddler, they took pride in my Shirley Temple prettiness and my ability to memorize long verses so I could impress their guests with my recitations. When I was in the early grades, my parents took pride in my ability to do well in school. By the time I was nine or ten, however, they didn’t pay much attention to me. By that time, I wasn’t much use to them, or so it seemed to me.

My parents continued to take good care of me as I moved through childhood and through adolescence and on into adulthood, but they left me to my own devices most of the time. I felt little or no emotional connection to either of my parents and regarded them as adversaries. They had molded and shaped my behavior into that which was acceptable to them, to the people they knew, and to society at large, but we had not connected on a human level. They didn’t know me as a person, and I didn’t know them. What’s more, I had the distinct sense that they did not want to know me as a person, and they did not want me to know them.

By the time I left home for college, they had done their job, that of caring for my physical needs, educating me, instilling in me the societal values of the time—yes, they had done everything they were obligated to do, or so they probably felt. They had, however, left to me the task of learning to develop a sense of attachment to other human beings.

I have always been aware at some level of my awareness that I have lacked something most of my friends seemed to possess, but only recently have I understood what that “something” has been. That “something” has been a sense of being “with” other people, of having a connection to other people. Only recently have I been aware that my old, old perception of me being on one side and everyone else being on the other side may not be an accurate perception. My therapist is working with me on this, trying to help me bridge this gap. And the latest brain research says that my brain has retained sufficient plasticity to enable me, at age seventy-two, to overcome this developmental gap.

I have hope that my therapist’s belief in my ability to overcome this gap and the knowledge that my brain is still plastic enough to make this change will enable me to see clearly that my old assumption of life being a case of “me versus them” is a concept with an expiration date, a developmental gap that is within my power to bridge.

A psychologist friend of mine frequently reminds me that with awareness comes change. I have learned through life that this belief is true. When I become aware of a problem or a condition or a difficulty in my life, then I am usually able to make a change for the better. Not being taught in infancy to connect securely with other people and not learning to believe that most people truly want to be supportive when they say they do have left their marks on my psyche and underlie my feeling of being isolated, but I need now to “put on my big girl panties” and work with my therapist to repair this developmental gap. It can be done, and I will do it! WE will do it! Together.

Note: After doing some heavy thinking about what I have said in this essay, I have realized that my reader may get the message that my parents' failure to connect with me is the sole reason for my difficulty as an adult to connect with others. That, I believe, is not entirely the case.

Many of us were raised in the first half of the 1900s when behaviorism strongly influenced child-raising theory, and a lot of young parents in this country bought into the same theory my parents accepted. Somehow, though, many of my peers, women my age, avoided experiencing the "me against the world" mind set that has fed my lifelong feeling of isolation and has made connecting with other people or bonding with people so difficult for me.

It could be that a lot of parents simply did not take the theory of the times as seriously as my parents did and did not apply it to the exclusion of addressing their children's emotional and spiritual needs--as my parents did. In addition, the traumatic events of my childhood and the fact that after these events, I had no trusted adult to whom I could turn for help and support no doubt intensified my feeling of isolation.

For almost my entire seventy-two years of life, the thought of suicide has dogged me daily. The fact that I'm still here is proof that I have not acted upon the thought, of course. However, just thinking about suicide has been enough to sap my energy. I realize now how different my life might have been if I had learned to bond as a baby, if the traumatic events had not happened, and if I'd had a trusted person to talk to when I was a child. Even if I'd had just one of these three elements, my life might have been different. For one thing, I might not have chosen an abuser for my husband.

I am, however, a pragmatist, inclined to take the view that the past, damaging as it may have been, is over and done. It's up to me to do what I need to do to shape my future into what I want it to be. I have done that in some respects. I entered graduate school at age fifty when I was finished raising my daughter, had a career which I loved, and then retired. I now live on the Social Security I had built up and a small monthly annuity payment from the pension fund to which I had contributed.

I am, however, not finished shaping my future. Now I am working on repairing the damages resulting from childhood neglect and abuse and from abuses I experienced during the twenty years I was married. Repairing these damages is a huge task, as any of you know if you have been in therapy and involved in doing the same thing I'm doing.

I write the articles for this blog because I want to let you know that repairing the damages is possible. Also, I want to give you information and share my own experience with you in the hope that whatever I have to say will somehow be helpful to you as you struggle. If, through my efforts, I can help you, then my efforts are richly rewarded.

What I would like from you, my readers, are your comments, suggestions for topics, and any ideas that would help me help you. Also, if you have ideas that would help me make my website http://www.jfairgrieve.com/ more useful to readers, please send me those ideas in the comment form on this blog. In addition, if any of you who have blogs would like a mutual posting of links--I list your link on my site and you reciprocate--I'm up for that! As the adage goes, "It takes a village . . . "

(More on this topic of developmental gaps as I progress. My next step in therapy is to start EMDR. www.emdr.com/ According to my therapist, as I go through EMDR, more developmental gaps will surface. When that happens, we will deal with them.)

My purpose in maintaining this blog is to provide encouragement for those of you who are trying to relieve your PTSD symptoms. Therapy works! Jean

Welcome to My Blog!

The purpose of my blog is to provide encouragement to those of you who are working to relieve your PTSD symptoms through therapy. Although I try hard to present my information in a way that will be least likely to trigger anyone's PTSD symptoms, I cannot be sure that this will not happen. If you are in extreme emotional distress, please contact your therapist or call 911. I am not a therapist; I am merely a writer who has PTSD and who, like some of you, is working hard to find relief. Therapy IS helping me find this relief, and I am trying to spread the word so others will get help! For more information on this topic, please see my website at http://www.jfairgrieve.com/. Best wishes . . . Jean

Therapy is revisiting the "Happy" in "Happy Birthday."

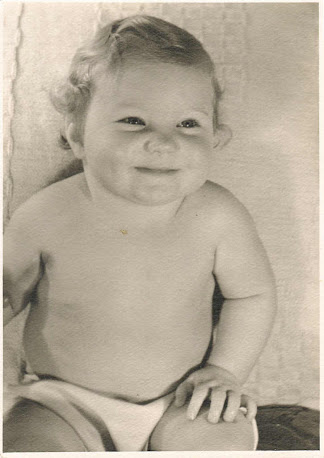

Jean, Age One

Wednesday, October 26, 2011

Friday, October 14, 2011

Developmental Gap?? What’s that??

If you have been reading the articles on this blog, you know that I’m being treated for Complex PTSD, C-PTSD. If you are not sure what C-PTSD is and how it differs from PTSD, my article on this blog titled “Complex PTSD: Does It Exist?” will give you information on this topic. In today’s article I plan to give you a bit more insight into the complexity of Complex PTSD. Since I am not a mental health professional but am merely a writer who is undergoing treatment for C-PTSD, I can’t do more than give you a small glimpse into the matter of “developmental gaps” as I become aware of them. But a small glimpse will lead to a larger glimpse as time goes by, and I will gladly give you more information as I acquire it.

I was born in 1939, a time prior to Dr. Spock and prior to such big names in the field of child development as Ilg, Ames, and Gesell. Yes, in 1939 many parents still followed the old “feed ‘em, burp ‘em, diaper ‘em, put ‘em in the crib, and don’t touch ‘em for four hours” school of child raising. Some parents prior to WWII also espoused the somewhat Victorian belief that children were “things” that did not become fully human until they finished puberty. A few American parents, including my own, bought into a more Calvinistic belief popular with some parents in Europe around the end of the 1700s and stretching into the pre-War 1900s. This philosophy stressed the belief that “rearing a child was a battle of wills between the inherently sinful infant or child and the parent.” *The child’s will, obviously, had to be crushed if the child was to mature into a law-abiding and responsible adult and a good citizen. *http://www.faqs.org/childhood/Bo-Ch/Child-Rearing-Advice-Literature.html

Another child-raising belief popular in Europe but also reaching its tentacles into our American culture prior to World War II can be stated as follows: “These first years have, among other things, the advantage that one can use force and compulsion. With age children forget everything they encountered in their early childhood. Thus if one can take away children's will, they will not remember afterward that they had had a will." Wickipedia. (Google “Moritz Schreber” and you will find the Wickipedia article. In the section titled “notes and references” click on the term “poisonous pedagogy.” This will take you to the page containing the sentiments quoted above. If you want to see the above philosophy of child rearing in action, see the film titled “The White Ribbon.”)

As you may imagine, by combining the Calvinistic view of raising children with the view that children “forget everything they encountered in their early childhood” as quoted above, a determined parent could effectively insure that a child’s development was as full of holes or gaps as a leaky collander—if the child lived to reach adulthood.

When I consider the beliefs described above and compare them with the child-rearing methods I’ve seen in the post-Spock era, I can see how horribly skewed the pre-War beliefs were--skewed on the side of adults to the neglect of children. By that I mean according to much of the literature of the times, children were not believed to be anything other than clay to be molded into creatures destined to fit the personal and social templates espoused by their parents. And since my mother espoused all the beliefs described in the quote above when she raised me, why should I be surprised that I’m being treated for Complex PTSD? Rather than regard me as a human infant who had normal human infant needs such as the need for parental nurturing and connection, she believed the official "wisdom" of the day and thought she was doing the right thing by treating me as an adversary, a creature needing nothing more than to be forced to conform to behavioral norms, hers and those of society. When I think of all the other people my age who were also raised by parents espousing the official child-rearing wisdom of the time, I shudder!

Furthermore, my mother never hesitated to pass on this “poisonous pedagogy” to the young mothers in the neighborhood. The women would regularly bring their infants and toddlers to our house for kaffeeklatsches, and my mother would pass on her wisdom as they listened eagerly. I was around the age of eleven when I heard her utter the following: “If you pick him up just because he’s crying, then you will have a spoiled baby who thinks he is boss. You need to break his will. If you do that, then he will be a happy baby. You don’t want him to be boss!”

Since I was about six when my brother was a baby, I can remember watching her apply these sentiments as she cared for him. I remember her fighting with my baby brother as he sat, a captive in his highchair, at mealtime. When he didn’t want to eat what she put on the spoon, for example, she tried to force the spoon into his closed mouth. When he refused to open, she slapped him and yelled at him. This caused him to cry, and then she was able to shove the food into his mouth. A victory for her! She had broken his will and had shown him she was boss! The struggle continued through the years and through all developmental stages. I could only assume that she applied these same principles as she cared for me when I was a baby.

Now, as an adult, I can understand why throughout my childhood and adulthood I regarded my mother as an adversary and never as an ally. I also understand why I learned to live a double life, one with my compliant self on the surface and my authentic self beneath the surface where she couldn’t reach me. Where was my father in this battle? Couldn’t he have helped me? My father left child raising to my mother. Sometimes he was the parent who did the punishing, but other than that, he did not participate in parenting me or my brother.

So how does the above discussion of child-rearing relate to the matter of developmental gaps discovered in adulthood? I can speak only from my own experience, but it’s possible that my experience will resonate in the hearts of other people who were born prior to WWII. My mother found her child-raising wisdom in a book published in the 1930s and distributed by the U. S. government. You can find information about this publication on the following website: http://www.faqs.org/childhood/Bo-Ch/Child-Rearing-Advice-Literature.html The stated purpose of this booklet was to provide parents with the information they needed to raise children who would grow into adults especially suited for working in our highly industrialized nation at the time. The following sentence from a paragraph on this site is particularly relevant to understanding the prevailing philosophy: "[John B.] Watson explicitly criticized 'too much mother love,' advising parents to become detached and objective in their child-rearing techniques so as to develop self-control in the child." For more information on the nature of this “wisdom,” please see the note at the end of this article.

Unfortunately for me, being raised “by the book” did not instill in me a sense of connection to other people. I remember when I was about eight years old saying to myself, “It’s me against everyone else in the world.” That’s the way life seemed to me, and that’s the way I have lived my life. Luckily, my children were part of “me” when I was a mother and not part of “everyone else,” at least until they were on their own as adults. Only in the past few weeks have I learned that my childhood attitude of “me against the rest of the world” is an attitude held by many children who have suffered neglect and other kinds of abuse and indicates that some aspect of learning how to connect with other human beings was derailed in babyhood and/or in childhood. In other words, I have discovered within myself a developmental gap. (End of Part I.)

Note: Here is the paragraph from the website cited in paragraph seven that contains the Watson warning concerning “too much mother love”:

"The behaviorism of JOHN B. WATSON and others provided the scientific psychology behind most ideas about child rearing in the 1920s and 1930s, though Freudian and other psychoanalytic ideas also enjoyed some popularity in these circles. Both approaches considered the first two or three years of life to be critical to child rearing. The behaviorist approach assumed that behavior could be fashioned entirely through patterns of reinforcement, and Watson's ideas permeated the Children's Bureau's Infant Care bulletins and PARENTS MAGAZINE, which was founded in 1926. As historians and others have observed, this approach to programming and managing children's behavior suited a world of rationalized factory production and employee management theories rationalizing industrial relations. Watson explicitly criticized 'too much mother love,' advising parents to become detached and objective in their child-rearing techniques so as to develop self-control in the child." (I’ve underlined and bolded what I consider to be the most important point in this paragraph.)

Coming soon: More information on this topic. I hope those of you who have discovered this particular gap or other gaps in your own development will find encouragement in reading this account of my own experience. With awareness comes the possibility of healing. Therapy helps!

I was born in 1939, a time prior to Dr. Spock and prior to such big names in the field of child development as Ilg, Ames, and Gesell. Yes, in 1939 many parents still followed the old “feed ‘em, burp ‘em, diaper ‘em, put ‘em in the crib, and don’t touch ‘em for four hours” school of child raising. Some parents prior to WWII also espoused the somewhat Victorian belief that children were “things” that did not become fully human until they finished puberty. A few American parents, including my own, bought into a more Calvinistic belief popular with some parents in Europe around the end of the 1700s and stretching into the pre-War 1900s. This philosophy stressed the belief that “rearing a child was a battle of wills between the inherently sinful infant or child and the parent.” *The child’s will, obviously, had to be crushed if the child was to mature into a law-abiding and responsible adult and a good citizen. *http://www.faqs.org/childhood/Bo-Ch/Child-Rearing-Advice-Literature.html

Another child-raising belief popular in Europe but also reaching its tentacles into our American culture prior to World War II can be stated as follows: “These first years have, among other things, the advantage that one can use force and compulsion. With age children forget everything they encountered in their early childhood. Thus if one can take away children's will, they will not remember afterward that they had had a will." Wickipedia. (Google “Moritz Schreber” and you will find the Wickipedia article. In the section titled “notes and references” click on the term “poisonous pedagogy.” This will take you to the page containing the sentiments quoted above. If you want to see the above philosophy of child rearing in action, see the film titled “The White Ribbon.”)

As you may imagine, by combining the Calvinistic view of raising children with the view that children “forget everything they encountered in their early childhood” as quoted above, a determined parent could effectively insure that a child’s development was as full of holes or gaps as a leaky collander—if the child lived to reach adulthood.

When I consider the beliefs described above and compare them with the child-rearing methods I’ve seen in the post-Spock era, I can see how horribly skewed the pre-War beliefs were--skewed on the side of adults to the neglect of children. By that I mean according to much of the literature of the times, children were not believed to be anything other than clay to be molded into creatures destined to fit the personal and social templates espoused by their parents. And since my mother espoused all the beliefs described in the quote above when she raised me, why should I be surprised that I’m being treated for Complex PTSD? Rather than regard me as a human infant who had normal human infant needs such as the need for parental nurturing and connection, she believed the official "wisdom" of the day and thought she was doing the right thing by treating me as an adversary, a creature needing nothing more than to be forced to conform to behavioral norms, hers and those of society. When I think of all the other people my age who were also raised by parents espousing the official child-rearing wisdom of the time, I shudder!

Furthermore, my mother never hesitated to pass on this “poisonous pedagogy” to the young mothers in the neighborhood. The women would regularly bring their infants and toddlers to our house for kaffeeklatsches, and my mother would pass on her wisdom as they listened eagerly. I was around the age of eleven when I heard her utter the following: “If you pick him up just because he’s crying, then you will have a spoiled baby who thinks he is boss. You need to break his will. If you do that, then he will be a happy baby. You don’t want him to be boss!”

Since I was about six when my brother was a baby, I can remember watching her apply these sentiments as she cared for him. I remember her fighting with my baby brother as he sat, a captive in his highchair, at mealtime. When he didn’t want to eat what she put on the spoon, for example, she tried to force the spoon into his closed mouth. When he refused to open, she slapped him and yelled at him. This caused him to cry, and then she was able to shove the food into his mouth. A victory for her! She had broken his will and had shown him she was boss! The struggle continued through the years and through all developmental stages. I could only assume that she applied these same principles as she cared for me when I was a baby.

Now, as an adult, I can understand why throughout my childhood and adulthood I regarded my mother as an adversary and never as an ally. I also understand why I learned to live a double life, one with my compliant self on the surface and my authentic self beneath the surface where she couldn’t reach me. Where was my father in this battle? Couldn’t he have helped me? My father left child raising to my mother. Sometimes he was the parent who did the punishing, but other than that, he did not participate in parenting me or my brother.

So how does the above discussion of child-rearing relate to the matter of developmental gaps discovered in adulthood? I can speak only from my own experience, but it’s possible that my experience will resonate in the hearts of other people who were born prior to WWII. My mother found her child-raising wisdom in a book published in the 1930s and distributed by the U. S. government. You can find information about this publication on the following website: http://www.faqs.org/childhood/Bo-Ch/Child-Rearing-Advice-Literature.html The stated purpose of this booklet was to provide parents with the information they needed to raise children who would grow into adults especially suited for working in our highly industrialized nation at the time. The following sentence from a paragraph on this site is particularly relevant to understanding the prevailing philosophy: "[John B.] Watson explicitly criticized 'too much mother love,' advising parents to become detached and objective in their child-rearing techniques so as to develop self-control in the child." For more information on the nature of this “wisdom,” please see the note at the end of this article.

Unfortunately for me, being raised “by the book” did not instill in me a sense of connection to other people. I remember when I was about eight years old saying to myself, “It’s me against everyone else in the world.” That’s the way life seemed to me, and that’s the way I have lived my life. Luckily, my children were part of “me” when I was a mother and not part of “everyone else,” at least until they were on their own as adults. Only in the past few weeks have I learned that my childhood attitude of “me against the rest of the world” is an attitude held by many children who have suffered neglect and other kinds of abuse and indicates that some aspect of learning how to connect with other human beings was derailed in babyhood and/or in childhood. In other words, I have discovered within myself a developmental gap. (End of Part I.)

Note: Here is the paragraph from the website cited in paragraph seven that contains the Watson warning concerning “too much mother love”:

"The behaviorism of JOHN B. WATSON and others provided the scientific psychology behind most ideas about child rearing in the 1920s and 1930s, though Freudian and other psychoanalytic ideas also enjoyed some popularity in these circles. Both approaches considered the first two or three years of life to be critical to child rearing. The behaviorist approach assumed that behavior could be fashioned entirely through patterns of reinforcement, and Watson's ideas permeated the Children's Bureau's Infant Care bulletins and PARENTS MAGAZINE, which was founded in 1926. As historians and others have observed, this approach to programming and managing children's behavior suited a world of rationalized factory production and employee management theories rationalizing industrial relations. Watson explicitly criticized 'too much mother love,' advising parents to become detached and objective in their child-rearing techniques so as to develop self-control in the child." (I’ve underlined and bolded what I consider to be the most important point in this paragraph.)

Coming soon: More information on this topic. I hope those of you who have discovered this particular gap or other gaps in your own development will find encouragement in reading this account of my own experience. With awareness comes the possibility of healing. Therapy helps!

Sunday, October 2, 2011

Denial and the Danger of Butterflies

In 1981, I attended a Life, Death, and Transition workshop held by Dr. Elisabeth Kubler-Ross at

As I listened to Dr. Kubler-Ross describe the butterflies, the concentration camp barracks, and the possible mental states of the prisoners, I felt a sort of deja-vu sensation. What Kubler-Ross was saying about the prisoners and their butterflies resonated within me. I realized, then, that my daughter and I had been prisoners in our own concentration camp, and I remembered my own butterfly.

At the end of summer in 1978, my family and I returned to

Now, some thirty years later, I can see the text-book dynamics of domestic violence at work—my isolation and lack of female friends in whom I could have confided, my fear of displeasing my husband and triggering his violent temper, and my inability to see that I was being abused. In 1980, I knew my life at home was not what I had hoped it would be when I married in 1961, but because I had no idea as to what behavior took place in the bedrooms of other women, I had no frame of reference, no way I could evaluate my own experience. Although I did not know it at the time, my mental state was much the same as that of the Jews described by Dr. Kubler-Ross: I denied the danger inherent in my situation, and I waited, expecting my situation to improve. To help me wait, I, like the Jews who drew on the walls of their barracks, painted an imaginary butterfly on my bedroom ceiling.

My butterfly was merely a piece of ragged wallpaper on the bedroom ceiling, but my imagination added details and glorious colors to that gray, torn bit of wallpaper until it became a beautiful Monarch. As I lay in bed, I would stare at the ceiling, willing my self to fly from my body and become one with that butterfly. As the months passed, I became more and more skilled at flying. I reached the point, in fact, where I flew to the ceiling whether I wanted to or not. My body could be making the bed, changing clothes, or doing whatever it was expected to do, but I was on the ceiling the whole time, velvet wings flapping, watching from above. One day, however, I caught myself in mid flight, understood where I was going, knew why I was going there, and realized that my flying had to cease.

How or why did I suddenly recognize the reality of my situation? I can only surmise that the fact I was in therapy had something to do with my sudden insight. A few months previous, I had begun seeing a therapist because I felt so fragmented that I had to talk myself through my daily routine in order to function effectively. Each step of the way, I had to tell myself aloud what I was doing or what I was supposed to do, including during my job as an insurance clerk. Luckily, other than my boss, who was out of the office much of the time, I was the only employee, and normally not many clients came in person to take care of their business. When somebody came in, I was able to greet the person, converse, and do what was expected. When I was alone, however, I was forced to resume my dialog in order to do filing or other paperwork. After living for about six months in this condition, I knew I needed help.

Thus, when I entered therapy, I believed that my increasing inability to think or reason effectively and clearly without talking myself through my day was a sign that my cognitive abilities were breaking down, but I did not connect this with the abuses I endured in my marriage. I worked hard in therapy, and my therapist was supportive and concerned. As time passed and I became more trusting of my therapist, I found myself beginning to think more clearly without having to talk myself through daily tasks. In addition, as thinking became easier, I became more and more aware of the chaos outside my head. In the bedroom, I flew to the ceiling less often, and I became less and less tolerant of my husband's rages, of his violence in the bedroom, and of his verbal abuse. I began telling him when I didn’t like what he was doing to me.

In addition to becoming more aware that I was being abused, I also let my husband know that I would not tolerate certain of his practices with our daughter. For example, rather than cringing in fear when he stood our daughter in the corner after dinner, shouted multiplication problems at her, and then cursed at her when she failed to give the correct response, I let him know that his behavior was abusive and unacceptable and had to stop. Although he did not completely stop this behavior, the after-dinner sessions became less frequent. Perhaps in response to my newly-exhibited assertiveness, his behavior changed—at least, that was my thought. He threw fewer tantrums, spoke more respectfully, and generally became less violent. He even asked me to buy our daughter some pretty dresses, something he had never done before. I happily assumed that our relationship was improving and that my husband was trying hard to control his volatile temper.

The change in my husband’s behavior caught me off guard. I relaxed around him and became more trusting. At this point, life looked good. My husband’s behavior toward our daughter and me was improving, so I thought, and I allowed myself to hope that in time, we would become a stable and loving family. Like the Jews lured into the gas chambers by promises of hot showers and clean clothing, I was seduced into believing that my husband’s outwardly changed behavior was an accurate indicator of his intentions. Thus, the truth of our situation hit me like a sucker punch when I walked in on him one spring evening in 1981 and caught him in the act of using our daughter for his own sexual pleasure.

Shortly after discovering the abuse and when I had my first chance to talk to my daughter without my husband being present, I learned that after we returned from Germany, he had begun grooming her for the abuse and had begun the abuse in earnest right after her eleventh birthday. Each time I left the house to shop or to run errands and left her home with him, she became his prey. And because our daughter had spent the first three years of her life being bounced from one foster home to another, she was especially vulnerable and eager to please him. She had no desire to displease him and risk being sent back into the foster care system.

Because her father had told her that if I learned of the abuse, I would be jealous and wouldn’t love her, my daughter was reluctant at first to give me any but the most general information regarding what had transpired between her and her father. After I reported my husband, however, and she realized that he and not she would no longer be living in our home, she gave me details of incidents. As the details emerged and I became progressively more horrified at the abuse she endured, my anger intensified. How could my husband have performed those atrocities on an innocent child, a child who had spent the first three years of her life in the foster care system, a child who needed so intensely to feel our love as her adoptive parents? How could he have been so, so selfish? How could he have been the person I was married to for twenty years? My anger and those questions swirled around my mind as I tended to the practical matters involved in establishing a new household, one in which I was the head and the sole parent of my thirteen-year-old daughter.

Thirty years later, I still can’t answer those questions. My daughter is grown and married. According to her, her life now is okay. I admire her. She is a good person, kind and loving despite the abuse she suffered. I’ve been on my own since that day in 1981 when I reported my former husband to the police. And since then, I’ve had no need for butterflies on my ceiling or for flying to join them.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)